The Class System in Sencha Touch 2 - What you need to know

Sencha Touch 1 used the class system from Ext JS 3, which provides a simple but powerful inheritance

Last week we unveiled a the brand new class system coming in Ext JS 4. If you haven’t seen the new system in action I hope you’ll take a look at the blog post on sencha.com and check out the live demo. Today we’re going to dig a little deeper into the class system to see how it actually works.

To briefly recap, the new class system enables us to define classes like this:

Here we’ve set up a slightly simplified version of the Ext.Window class. We’ve set Window up to be a subclass of Panel, declared that it requires the Ext.Tool class and that it mixes in functionality from the Ext.util.Draggable class.

There are a few new things here so we’ll attack them one at a time. The ‘extend’ declaration does what you’d expect - we’re just saying that Window should be a subclass of Panel. The ‘requires’ declaration means that the named classes (just Ext.Tool in this case) have to be present before the Window class can be considered ‘ready’ for use (more on class readiness in a moment).

The ‘mixins’ declaration is a brand new concept when it comes to Ext JS. A mixin is just a set of functions (and sometimes properties) that are merged into a class. For example, the Ext.util.Draggable mixin we defined above might contain a function called ‘startDragging’ - this gets copied into Ext.Window to enable us to use the function in a window instance:

When we create a new Ext.Window instance now, we can call the function that was mixed in from Ext.util.Draggable:

Mixins are really useful when a class needs to inherit multiple traits but can’t do so easily using a traditional single inheritance mechanism. For example, Ext.Windows is a draggable component, as are Sliders, Grid headers, and many other UI elements. Because this behavior crops up in many different places it’s not feasible to work the draggable behavior into a single superclass because not all of those UI elements actually share a common superclass. Creating a Draggable mixin solves this problem - now anything can be made draggable with a couple of lines of code.

The last new piece of functionality I’ll mention briefly is the ‘config’ declaration. Most of the classes in Ext JS take configuration parameters, many of which can be changed at runtime. In the Ext.Window above example we declared that the class has a ‘title’ configuration, which takes the default value of ‘Window Title’. By setting the class up like this we get 4 methods for free - getTitle, setTitle, resetTitle and applyTitle.

The applyTitle function is the place to put any logic that needs to be called when the title is changed - for example we might want to update a DOM Element with the new title:

This saves us a lot of time and code while providing a consistent API for all configuration options: win-win.

Ext JS 4 introduces 4 new classes to make all this magic work:

These all work together behind the scenes and most of the time you won’t even need to be aware of what is being called when you define and use a class. The two functions that you’ll use most often - Ext.define and Ext.create - both call Ext.ClassManager under the hood, which in turn utilizes the other three classes to put everything together.

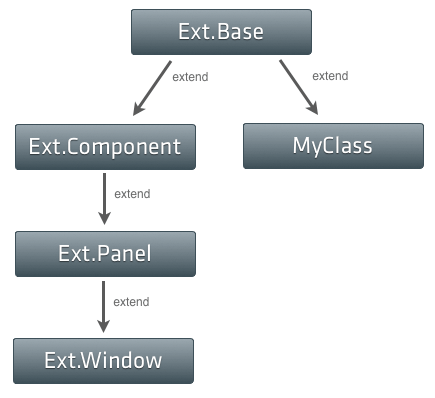

The distinction between Ext.Class and Ext.Base is important. Ext.Base is the top-level superclass for every class ever defined - every class inherits from Ext.Base at some point. Ext.Class represents the class itself - every class you define is an instance of Ext.Class, and a subclass of Ext.Base. To illustrate, let’s say we created a class called MyClass, which doesn’t extend any other class:

The direct superclass for MyClass is Ext.Base because we didn’t specify that MyClass should extend anything else. If you imagine a tree of all the classes we’ve defined so far, it will look something like this:

This tree bases its hierarchy on the inheritance structure of our classes, and the root is always Ext.Base - that is, every class eventually inherits from Ext.Base. So every item in the diagram above is a subclass of Ext.Base, but every item is also an instance of Ext.Class. Classes themselves are instances of Ext.Class, which means we can easily modify the Class at a later time - for example mixing in additional functionality:

This architecture opens up new possibilities for dynamic class creation and metaprogramming, which were difficult to pull off in earlier versions.

In the next episode, we’ll look at how the class definition pipeline is structured and how to extend it to add your own features.

For an in-depth understanding of how classes are managed and constructed in Ext JS 4, check out Ext JS 4: The Class Definition Pipeline, which explores the intricacies of the class creation process. Additionally, Ext.override - Monkey Patching Ext JS offers insights into modifying existing classes, while Custom containers with ExtJS provides guidance on extending container functionality for more complex user interfaces.

Sencha Touch 1 used the class system from Ext JS 3, which provides a simple but powerful inheritance

Last time, we looked at some of the features of the new class system in Ext JS 4, and explored some

A few days back Praveen Ray posted about 'Traits' in Ext JS. What he described is pretty much what