It's been quite some time since I've published anything under the "sencha" tag, with the most recent posts dating back over a decade. Revisiting these older articles is a chance to reflect on the strides we made in the early days of Sencha. At Sencha Con 2013, discussions were vibrant around performance tips and developments like Fastbook, which was aimed at enhancing app performance using HTML5.

Back in 2012, there was significant buzz around the release of Sencha Touch 2, which I explored in pieces like Anatomy of a Sencha Touch 2 App and the beta release coverage in Sencha Touch 2 Hits Beta. These posts dive into the framework's structure and its potential for mobile web applications, providing foundational insights that paved the way for many developers tackling Sencha and Ext JS.

Sencha Con 2013 Wrapup

So another great Sencha Con is over, and I'm left to reflect on everything that went on over the last few days. This time was easily the biggest and best Sencha Con that I've been to, with 800 people in attendance and a very high bar set by the speakers. The organization was excellent, the location fun (even if the bars don't open until 5pm...), and the enthusiasm palpable.

I've made a few posts over the last few days so won't repeat the content here - if you want to see what else happened check these out too:

What I will do though is repeat my invitation to take a look at what we're doing with JavaScript at C3 Energy. I wrote up a quick post about it yesterday and would love to hear from you - whether you're at Sencha Con or not.

Now on to some general thoughts.

Content

There was a large range in the technical difficulty of the content, with perhaps a slightly stronger skew up the difficulty chain compared to previous events. This is a good thing, though there's probably still room for more advanced content. Having been there before though, I know how hard it is to pitch that right so that everyone enjoys and gets value of out it.

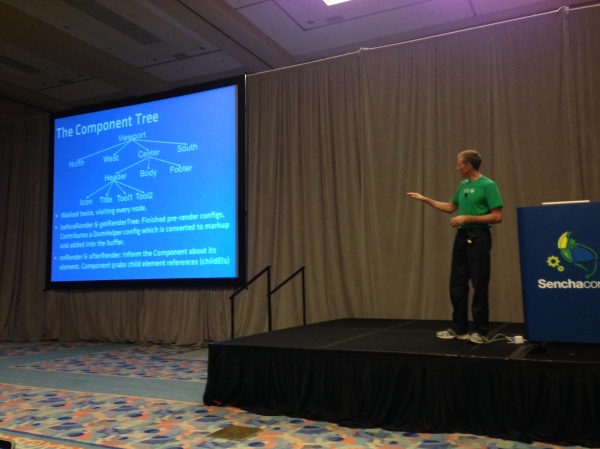

Sencha Con 2013: Ext JS Performance tips

Just as with Jacky's session, I didn't plan on making a separate post about this, but again the content was so good and I ended up taking so many notes that it also warrants its own space. To save myself from early carpal tunnel syndrome I'm going to leave this one in more of a bullet point format.

Ext JS has been getting more flexible with each release. You can do many more things with it these days than you used to be able to, but there has been a performance cost associated with that. In many cases this performance degradation is down to the way the framework is being used, as opposed to a fundamental problem with the framework itself.

There's a whole bunch of things that you can do to dramatically speed up the performance of an app you're not happy with, and Nige "Animal" White took us through them this morning. Here's what I was able to write down in time:

Slow things

Nige identified three of the top causes of sluggish apps, which we'll go through one by one:

- Network latency

- JS execution

- Layout activity

Sencha Con 2013: Fastbook

I didn't plan on writing a post purely on Fastbook, but Jacky's presentation just now was so good I felt it needed one. If you haven't seen Fastbook yet, it is Sencha's answer to the (over reported) comments by Zuckerburg that using HTML5 for Facebook's mobile app was a mistake.

After those comments there was a lot of debate around whether HTML5 is ready for the big time. Plenty of opinions were thrown around, but not all based on evidence. Jacky was curious about why Facebook's old app was so slow, and wondered if he could use the same technologies to achieve a much better result. To say he was successful would be a spectacular understatement - Fastbook absolutely flies.

Performance can be hard to describe in words, so Sencha released this video that demonstrates the HTML5 Fastbook app against the new native Facebook apps. As you can see, not only is the HTML5 version at least as fast and fluid as the native versions, in several cases it's actually significantly better (especially on Android).

Anatomy of a Sencha Touch 2 App

At its simplest, a Sencha Touch 2 application is just a small collection of text files - html, css and javascript. But applications often grow over time so to keep things organized and maintainable we have a set of simple conventions around how to structure and manage your application's code.

A little while back we introduced a technology called Sencha Command. Command got a big overhaul for 2.0 and today it can generate all of the files your application needs for you. To get Sencha Command you'll need to install the SDK Tools and then open up your terminal. To run the app generator you'll need to make sure you've got a copy of the Sencha Touch 2 SDK, cd into it in your terminal and run the app generate command:

This creates an application called MyApp with all of the files and folders you'll need to get started generated for you. You end up with a folder structure that looks like this:

Sencha Touch 2 Hits Beta

Earlier today we released Sencha Touch 2 Beta 1 - check out the official sencha.com blog post and release notes to find out all of the awesome stuff packed into this release.

This is a really important release for us - Sencha Touch 2 is another huge leap forward for the mobile web and hitting beta is a massive milestone for everyone involved with the project. From a personal standpoint, working on this release with the amazing Touch team has been immensely gratifying and I hope the end result more than meets your expectations of what the mobile web can do.

While you should check out the official blog post and release notes to find out the large scale changes, there are a number of things I'd really like to highlight today.

A Note on Builds

Before we get into the meat of B1 itself, first a quick note that we've updated the set of builds that we generate with the release. Previously there had been some confusion around which build you should be using in which circumstances so we've tried to simplify that.

The Class System in Sencha Touch 2 - What you need to know

Sencha Touch 1 used the class system from Ext JS 3, which provides a simple but powerful inheritance system that makes it easier to write big complex things like applications and frameworks.

With Sencha Touch 2 we've taken Ext JS 4's much more advanced class system and used it to create a leaner, cleaner and more beautiful framework. This post takes you through what has changed and how to use it to improve your apps.

Syntax

The first thing you'll notice when comparing code from 1.x and 2.x is that the class syntax is different. Back in 1.x we would define a class like this:

This would create a subclass of Ext.Panel called MyApp.CustomPanel, setting the html configuration to 'Some html'. Any time we create a new instance of our subclass (by calling new MyApp.CustomPanel()), we'll now get a slightly customized Ext.Panel instance.

Sencha Touch 2 - Thoughts from the Trenches

As you may have seen, we put out the first public preview release of Sencha Touch 2 today. It only went live a few hours ago but the feedback has been inspiring so far. For the full scoop see the post on the sencha.com blog. A few thoughts on where we are with the product:

Performance

Performance on Android devices in particular is breathtaking. I never thought I'd see the day where I could pick up an Android 2.3 device and have it feel faster than an iPhone 4, and yet that's exactly what Sencha Touch 2 brings to the table. I recorded this short video on an actual device to show real world performance:

Now try the same on Sencha Touch 1.x (or any other competing framework) and (if you're anything like me) cringe at what we were accustomed to using before. That video's cool, but the one that's really driving people wild is the side by side comparison of the layout engines in 1.x and 2.x.

Getting our hands on a high speed camera and recording these devices at 120fps was a lot of fun. Slowing time down to 1/4 of normal speed shows just how much faster the new layout engine is than what we used to have:

Proxies in Ext JS 4

One of the classes that has a lot more prominence in Ext JS 4 is the data Proxy. Proxies are responsible for all of the loading and saving of data in an Ext JS 4 or Sencha Touch application. Whenever you're creating, updating, deleting or loading any type of data in your app, you're almost certainly doing it via an Ext.data.Proxy.

If you've seen January's Sencha newsletter you may have read an article called Anatomy of a Model, which introduces the most commonly-used Proxies. All a Proxy really needs is four functions - create, read, update and destroy. For an AjaxProxy, each of these will result in an Ajax request being made. For a LocalStorageProxy, the functions will create, read, update or delete records from HTML5 localStorage.

Because Proxies all implement the same interface they're completely interchangeable, so you can swap out your data source - at design time or run time - without changing any other code. Although the local Proxies like LocalStorageProxy and MemoryProxy are self-contained, the remote Proxies like AjaxProxy and ScriptTagProxy make use of Readers and Writers to encode and decode their data when communicating with the server.

Offline Apps with HTML5: A case study in Solitaire

One of my contributions to the newly-launched Sencha Touch mobile framework is the Touch Solitaire game. This is not the first time I have ventured into the dizzying excitement of Solitaire game development; you may remember the wonderful Ext JS Solitaire from 18 months ago. I'm sure you'll agree that the new version is a small improvement.

Solitaire is a nice example of a fun application that can be written with Sencha Touch. It makes use of the provided Draggables and Droppables, CSS-based animations, the layout manager and the brand new data package. The great thing about a game like this though is that it can be run entirely offline. Obviously this is simple with a native application, but what about a web app? Our goal is not just having the game able to run offline, but to save your game state locally too.

The answer comes in two parts:

Web Storage and the Sencha data package

HTML5 provides a brand new API called Web Storage for storing data locally. You can read all about it on my Web Storage post on Sencha's blog but the summary is that you can store string data locally in the browser and retrieve it later, even if the browser or the user's computer had been restarted in the meantime.